In grammatical terms, Mercury arrives in Libya before he even has flown there. Here, however, it appears that he wishes to indicate that a god moves faster than time.

#Scansion of aeneid full#

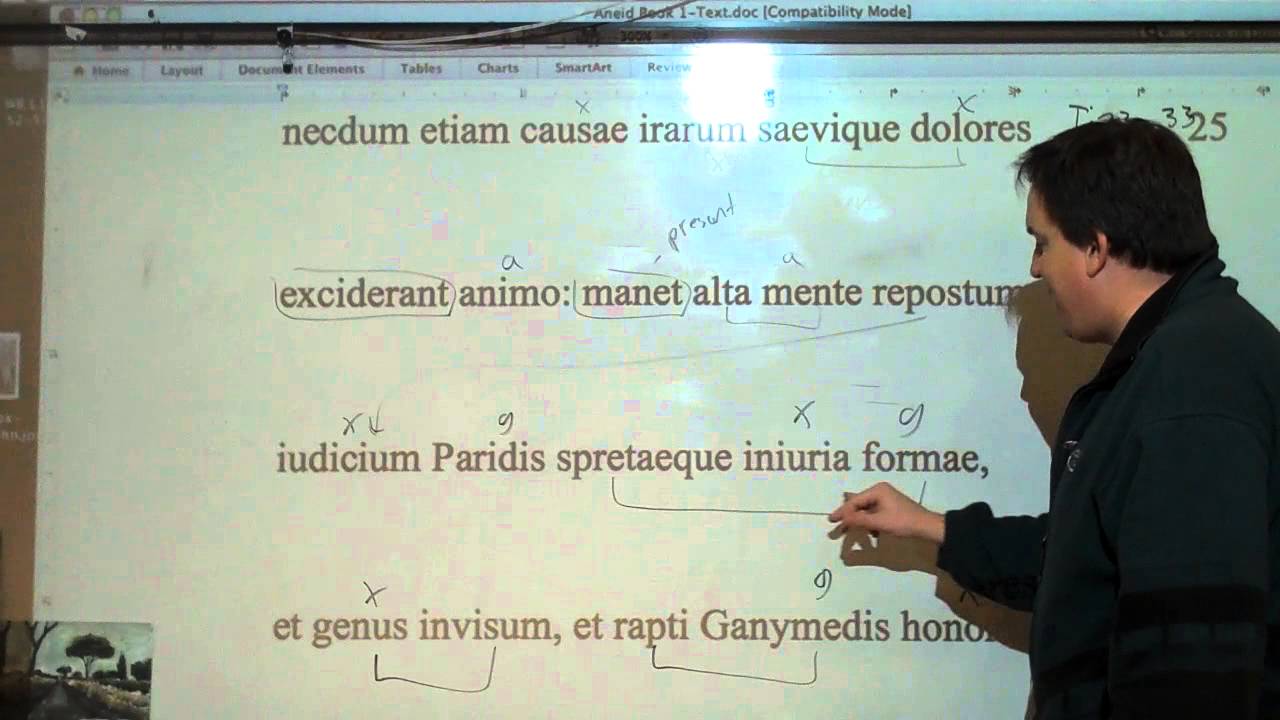

"He flies through the great air with a rowing of wings and swiftly stood on the shores of Libya." Sometimes it is difficult to grasp what purpose-if any-Vergil has in his selection of tenses. The text also includes a general introduction, a select bibliography, notes and a full vocabulary appendices deal with meter and scansion. murmur, uris, n.: a murmur, 6.709 uproar, 1.124 roaring, reverberation, 1.55. "Volat ille per āera magnum rēmigiō ālārum ac Libyae citus astitit ōrīs." intere: (adv.), amid these things meanwhile, in the meantime, 1.418, et al. "Smiling down at her (for 'illī'), the father" Since it is an ancient epic, The Aeneid is in dactylic hexameters, which is a meter the AP exams typically expect you to know. Let's assume you have a text of the beginning of The Aeneid with macrons. Middle voice (looks passive but = reflexive) To learn to scan a line of Latin poetry, it helps to know the meter and to use a text that shows the macrons. "filled with tears with respect to her bright eyes," i.e., "her bright eyes filled with tears" "for thus this people would be easy in living through the ages" Interesting Grammatical Features in Aeneid 1 These grammatical features are not necessarily stylistic devices, but may be less common than those topics typically covered in basic Latin. O Doomed Troy-all these may be translated "Troy" Yay! The Trojans-all these may be translated "Trojan" Used by itself to refer to the most important figure, i.e., Aeneasīoo! The Greeks-all these may be translated "Greek" Although there may be certain anthropological or geographical distinctions between one name and another, for our purposes they are identical.

It is helpful in reading the Aeneid to know that Vergil uses multiple names to refer to the same characters, groups, and places. I am a 6th year latin student, also taking Vergil this year, so were in the same boat.) First of all, the entire Aeneid is dactylic hexameter. The word hexameter also derives from Greek and essentially means "six metrons (or, to be precise, metra ) in a row." In other words, a single epic verse consists of six successive dactyls, as Figure B shows.Useful Proper Names from the Aeneid Introductory Comment The dactyl serves as the basic rhythmic unit, or metron, of hexameter verse. Recent scholars prefer to use 'long' and 'short' only for the 'natural' vowel. In recitation, the dactyl usually sounds like "dum-diddy," with "dum" equal to, and "diddy" to. But for the purposes of scansion the a in both words will receive a macron. In rhythmic terms, the two short syllables are equivalent in tempo to the long syllable, just as in music two half notes equal one whole note (or two eighths equal one quarter, and so on). The finger-like (dactylic) shape of the dactyl. Figure A will illustrate the concept better than any further remarks.

#Scansion of aeneid plus#

It has a rhythmic shape consisting of one long syllable (noted as ), which represents the long bone, or phalanx, of the finger, plus two short syllables ( ), which represent the two short phalanges. The dactyl is therefore a snippet of rhythm that resembles, at least aurally, a finger. The word dactylos is Greek for "finger" (and for "toe" as well, which picks up on the notion of feet, below). This was not the practice in Vergil's day, when the spoken word was preferred.) Fingers. (It is true that in Homer's era, epics were more sung than recited, to the accompaniment of a lyre. That is, it is impossible to conceive of an epic poem not composed in hexameters and the hexameter rhythms, when heard, signal that the poem being recited is an epic of some sort. It is fair to say that the dactylic hexameter defines epic.

#Scansion of aeneid manual#

Epic poetry from Homer on was recited in a particular meter called the dactylic hexameter. Scansion of Latin Dactylic Hexameter with Manual Adjustment Jun 2020 - Aug 2022 A Java program that scans Latin dactylic hexameter poetry, and a website coded from HTML + CSS explaining how it works. Greek and Latin poems follow certain rhythmic schemes, or meters, which are sometimes highly defined and very strict, sometimes less so. Before plunging into the technical details, a few introductory words are in order. As such, some liberties have been taken for the sake of clarity but with these principles in mind, students should be able to approach with some confidence the daunting prospect of reading Latin epic aloud. What follows is not a complete discussion of hexameter verse, but a utilitarian guide to the first principles of recitation. Introduction to the Dactylic Hexameter Preface.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)